Between Worlds: Honeybees as Divine Mediators in Neolithic and Classical Mythology

In our "Gimbutas and Goddesses" series, Pacifica graduate student Tamara Wolfson traces the sacred role of the honeybee as a divine mediator in Neolithic and Classical mythology

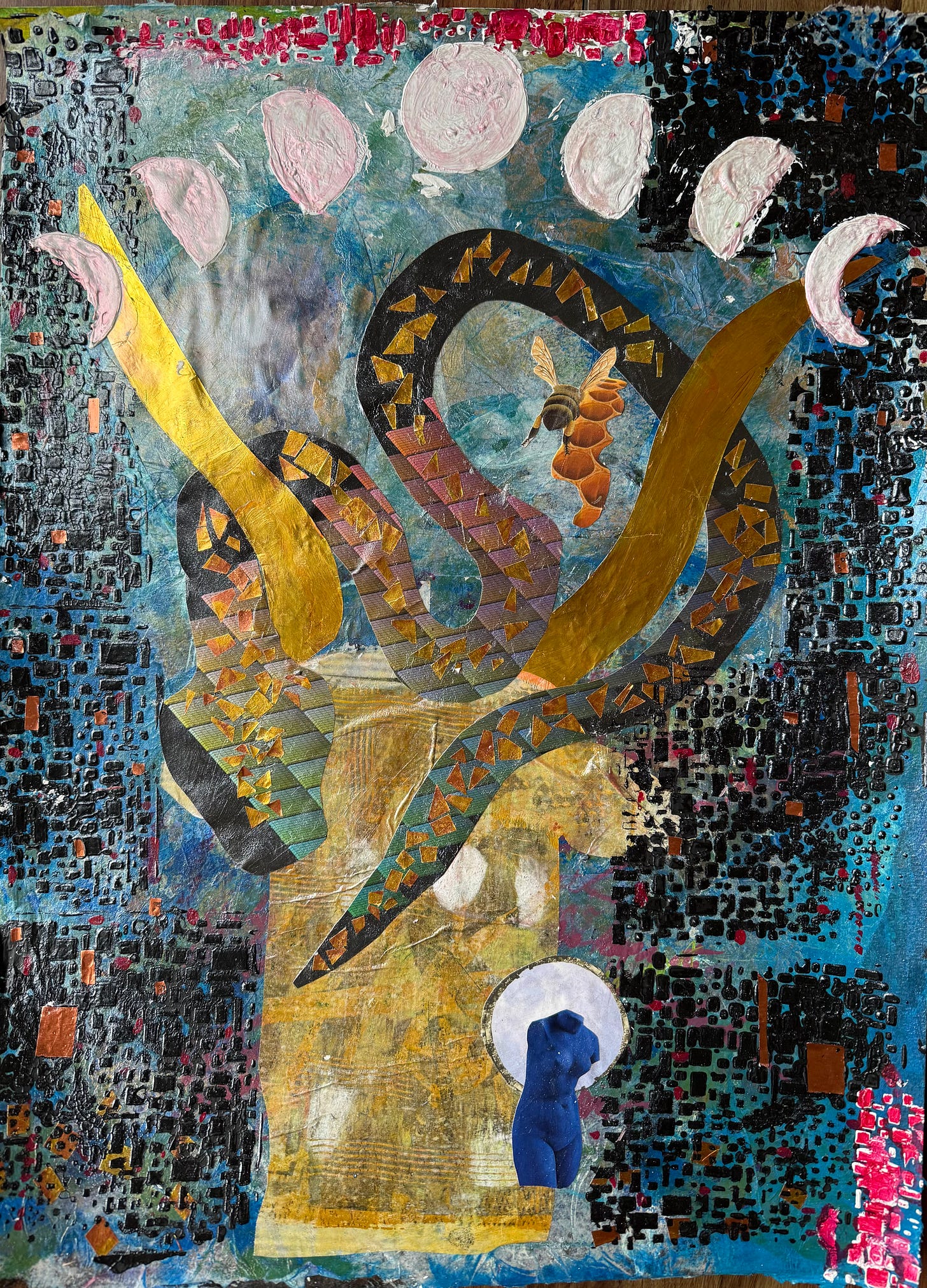

Apis and Ophidia, Alchemy of the Goddess, 2025, acrylic and gesso on paper, 18” x 24”, www.tamarawolfson.com

I was recently at the OPUS Archives to explore the honeybee's sacred role in mythology, particularly within early goddess cults of the Neolithic period (circa 7000/6000-3000 B.C.), where I found myself immersed in the revolutionary work of Marija Gimbutas. Her rich archaeological findings and feminine based interpretations offer unique insights into a time when the bee participated as a powerful symbol within the spiritual landscape of Old Europe. Gimbutas’ extensive documentation of artifacts, symbols, and cultural patterns demonstrates a worldview where the honeybee served as a bridge between the visible world and the divine feminine mysteries, deepening our modern understanding of ancient consciousness and ecological relationships. I was surprised to discover that through her work, the honeybee is intimately linked to the mythological origins of the gorgon. As unexpected as this may initially seem, a closer examination reveals that Medusa herself bears the wings of Apis mellifera, the honeybee, a connection that reconfigures our understanding of this misunderstood chthonic deity and her relationship to life's sweetness and sting.

In tracing the earliest European examples of the bee, I encountered not scientific schemas of biological organization, but curious images that suggest a profoundly different mindset in the relationship between humans and the world of nature. Gimbutas explains, "In Neolithic Europe and Asia Minor (ancient Anatolia)—in the era between 7000B.C. and 3,000B.C.—religion focused on the wheel of life and its cyclical turning" (3). In The Living Goddesses, she paints us a picture of an integrated relationship with the wild, one where animal, insect, and human share reciprocal experience and deterministic manifestation. Their looking glass world suggested that human regeneration, fertility, birth, life, and death depended on natural forces manifesting the same characteristics, an ancestral doctrine of signatures. This was an age that predates the rupture of humans’ overpowering nature, of the human appropriation of nature and nature as an object of subjugation. This was a time when nature, her rhythms, and seasons, were embodied as epistemic knowledge systems vital to human survival and as such were intensely observed and navigated. The challenges of fertility, childbirth, and childrearing, compounded by predation, nutritional deficiency, sickness, and infection, likely resulted in significant emphasis being placed on women's roles and their relationship with divine female collaboration for support. Throughout the artifacts of the Neolithic period, goddess figures and goddess structures dominated the European landscape, illuminating this essential partnership between the feminine divine and human survival.

What Gimbutas observed as a metaphoric thread throughout these archaeological sites was that birth was sacred. At Çatal Hüyük in south central Turkey, we find ancient birthing rooms painted red to represent blood, the "color of life." Figurines squatting with engorged vulvas appear for more than 20,000 years, from the Upper Paleolithic through the Neolithic period. These figures often appear in triadic formations, suggesting early manifestations of the Moirai, the three Fates of later Greek mythology, connecting women's reproductive capacity with cosmic power over life's duration and destiny.

Birth was associated with water, moisture, and aquatic sources such as rivers, lakes, rain, and springs, offering a natural parallel to the breaking of the amniotic sac announcing the imminence of new life. Gimbutas found that the net was also connected with water, birth fluids, as were "snakes, bears, frogs, fish, bulls' heads and rams' heads" (12). The bear as divine mother reaches as far back as the Upper Paleolithic. Observation of her winter hibernation and emergence from her cave with new life (cubs) consequently associated the bear with a pattern of birth, death, and rebirth. In Greek mythology, the bear is considered an incarnation of Artemis, and there is a plethora of European folk tales that connect the bear with birth and the ferocity of motherhood she exemplifies.

Birds and bird eggs similarly symbolize fertility, life-giving power, and prosperity. Birds and bears share a psychological association with natural cycles; bird migrations must have been particularly mysterious as species would disappear for the winter and reappear in spring, reinforcing the idea of death followed by renewal and rebirth. Additionally, the snake exhibits similar cyclical patterns, hibernating in the earth during winter and returning in spring, and the molting of snakeskin contributed to the symbolism of growth and transformation. Often the goddess was shown as a hybrid creature, part vulture or raptor in her devouring role, linking birth with death and death with birth. At Çatal Höyük, we see raptor goddesses with human feet and birds with human breasts and vulvas, further emphasizing this integration of human and animal aspects in the divine feminine.

The serpents that appear so prominently in Neolithic goddess imagery carry profound symbolic significance. As anthropologist Jeremy Narby suggests in The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge, these twining serpents may symbolize "the spiraling helixes of DNA and the origins of all humans" (93). The serpents twined around the heads, arms, and waists of goddesses represent the cycles of immortal existence through birth, life, death, and resurrection, a perfect complement to the bee's similar associations with cyclical life processes. These serpent symbols carried by the Great Goddesses symbolize life itself, making their later demonization in Western patriarchal traditions even more significant as a symbolic suppression of feminine power and regenerative capacity.

The snake goddess abounded in Neolithic art, squatting figures with snake-shaped limbs or snakeheads, as well as goddesses with snake coils or diamond bands imitating snakeskin prevalent as symbols of fecundity. Importantly, these feminine forces manifested not only life-giving qualities but were also associated with death, decay, and regeneration. The snake goddess also shows up in some of the oldest masks found in the Varna cemetery of eastern Bulgaria on the Black Sea. These frightening snake masks were covered in ornamental jewelry such as stones, bones, gold beads, and buried with spinning whorls, deer teeth and eggs, suggesting rituals of regeneration. Vases from Sultana in Southern Romania show a "horrific face, exposed teeth, and lolling tongue…the ancestors of the frightening Gorgon" (24). The Sultana vase also contains illustrations of a vulva, crescents, spirals, bird feet and double egg. The Gorgon imagery extends back 6,000 years to Thessaly in northern Greece. And we see her in ancient Greece in the seventh to the fifth centuries B.C. with the grinning mask, pendant tongue with the addition of bee wings alongside the life symbols of snakes, vines, lizards, cranes, and spirals.

According to Greek literature, the blood that dripped from Medusa's severed head could create life and rebirth, while the second drop brings death to destroy life. Gimbutas suggested this may have been associated with women's menstrual blood. Her head was then "appropriated for the aegis," a "badge of divine power" intended as a protective shield. The Gorgon has been found on many public and private buildings as protection, on coins, seals, and warrior shields such as that of the Goddess Athena (26).

What emerges from a deeper exploration of the honeybee in ancient Greek mythology is a remarkable dual function that extends beyond its connection to the Gorgon. Whispers of a forgotten intimate relationship, humming in the margins of our classical texts, reveal that bees served as unique messengers between the realms of men and gods in two distinct modes. Firstly, the bees supported the goddesses Demeter, Persephone, and Hekatē during the symbolic death experiences of initiatory rites that occurred, for example, during the Eleusinian Mysteries. Secondly, they were important as an escort for the dead to the underworld, alongside both Hermes and Hekatē. As chthonic immortals, these gods were all psychopomps, offering a kind escort on the bridge between the worlds.

This role aligns perfectly with the bee's natural characteristics. A beehive exists in a constant state of death and rebirth, with worker bees living on average about a month and the queen living approximately three years. The colony, however, can survive for decades, cycling through the births and deaths of workers and queens. Daily, a queen lays between one and two thousand eggs, surrounded simultaneously by the deaths of thousands of bees. As a superorganism, the beehive approaches immortality while remaining enmeshed in the death process, making it a perfect natural symbol for the transition between life and death.

This connection manifests architecturally in the beehive-shaped Mycenaean tholos tombs, suggesting the supportive influence of bees during the transition of death. The tombs physically embody the belief in the bee's role as guide and companion to the deceased soul. The association between bees and the soul's journey appears in classical philosophy as well. In Jowett's translation of Phaedrus, Plato describes the soul in relationship to wings:

The soul in her totality has the care of inanimate being everywhere, and traverses the whole heaven in divers forms appearing--when perfect and fully winged she soars upward, and orders the whole world; whereas the imperfect soul, losing her wings and drooping in her flight at last settles on the solid ground-there, finding a home, she receives an earthly frame which appears to be self-moved, but is really moved by her power; and this composition of soul and body is called a living and mortal creature.

He continues with:

The wing is the corporeal element which is most akin to the divine, and which by nature tends to soar aloft and carry that which gravitates downwards into the upper region, which is the habitation of the gods. The divine is beauty, wisdom, goodness, and the like; and by these the wing of the soul is nourished and grows apace; but when fed upon evil and foulness and the opposite of good, wastes and falls away.

This philosophical framing reinforces the bee's symbolic function as a bridge between earthly and divine realms. Just as the winged bee travels between flowers and hive, the winged soul journeys between mortal and immortal domains. The bee emerges as an archetypal conduit for what Carl Jung would later describe as a daimon, an inner guiding force that connects us to our source of inner intelligence and healing, urging us toward self-discovery and meaning.

We also find bees associated with sacred portals, most notably in the Cave of Nymphs in Homer's Odyssey, Book 13. Here, the honeybee and honey are described in connection with a womb-like cave on Ithaca with flowing life-giving water that is perpetually gliding, suggesting endless cycles for both mortal and immortal souls:

High at the head a branching olive grows /And crowns the pointed cliffs with shady boughs. / A cavern pleasant, though involved in night, / Beneath it lies, the Naiads delight: / Where bowls and urns of workmanship divine / And massy beams in native marble shine; / On which the Nymphs amazing webs display, / Of purple hue and exquisite array, / The busy bees within the urns secure / Honey delicious, and like nectar pure. / Perpetual waters through the grotto glide, / A lofty gate unfolds on either side; / That to the north is pervious to mankind: / The sacred south t'immortals is consign'd (lines 102-12).

This cave serves as a gateway for transitions between realms, "involved with night" yet "pleasant," reminiscent of Hekatē's cave in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. The bees' presence in this liminal space reinforces their role as guides between worlds.

In classical Greek understanding, bees functioned as what Plato described as daimons, intermediate spirits and messengers of divine will. He writes:

They are messengers who shuttle back and forth between the two, conveying prayer and sacrifice from men to gods, while to men they bring commands from the gods and gifts in return for sacrifices. Being in the middle of the two, they round out the whole and bind fast the all to all. Through them all divination passes, through them the art of priests in sacrifice and ritual, in enchantment, prophesy, and sorcery.

Here we see the bee's mythological function as mediator between realms, carrying messages between mortal and divine spheres. Their honey, produced in darkness but bringing sweetness and light, embodies this liminal quality, being neither fully of earth nor fully of heaven.

In classic Greek literature, the honeybee emerges as a unique contributor to both the landscape of the living and the terrain of the underworld. Through their presence, we are reminded of the cycles of death and rebirth, a knowledge which opens us to profound understanding of our interconnectedness with the earth and our own well-being. Through their alliance with chthonic gods and goddesses, from the fearsome Gorgon with her bee wings to the psychopomps Hermes and Hekatē, the honeybee becomes essential to understanding the Eleusinian mysteries and ancient Greek attitudes toward death and transformation.

The honeybee's journey from Neolithic goddess worship through classical Greek mythology reveals a consistent thread: these remarkable creatures have always served as bridges between worlds, whether between life and death, mortal and divine, or conscious and unconscious realms. In the space between opposing forces, these golden-winged messengers remind us to trust in the natural world, in our alignment with the divine fabric of life, and its ability to reveal our deepest wisdom.

This ancient understanding of the bee as mediator and messenger takes on renewed significance in our contemporary world. As we face ecological crises and the alarming decline of bee populations globally, we might recognize that the collapse of these ancient messengers threatens more than our food systems, it severs a symbolic and spiritual connection that has guided human consciousness for millennia. The bee's dual nature, bringing both sweetness through honey and pain through its sting, mirrors our own complex relationship with nature: its capacity to nurture but also to punish misuse and exploitation.

Perhaps in recovering these forgotten sacred associations, we can rediscover the bee not merely as a pollinator or honey producer, but as a guide in navigating our own transitions between states of being. Just as the ancient Greeks saw in the bee a psychopomp escorting souls between worlds, or as a winged Gorgon protectress, we might see in their plight a warning about our own disconnection from cycles of renewal and regeneration. The bee's ancient symbolism offers us a ecological wisdom: that life and death are not opposites but complementary phases in an eternal cycle, and that our well-being depends on honoring and protecting the messengers that connect these realms. In saving the bees, we may be preserving not just a keystone species, but an ancient archetype that has oriented human consciousness toward reverence for life's sacred continuity since our earliest awareness.

Winged Gorgon with volute nose, wide mouth, tusks/fangs, tongue, and beard, as Mistress of Animals flanked by geese; plate from Kameiros, Rhodes, British Museum A 748 (late seventh century BC)[69]

Works Cited

Gimbutas, Marija. The Living Goddesses. Edited by Miriam Robbins Dexter, University of California Press, 1999.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin Classics, 1996.

Narby, Jeremy. The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998.

Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017.

![Fig. 3. Winged Gorgon with volute nose, wide mouth, tusks/fangs, tongue, and beard, as Mistress of Animals flanked by geese; plate from Kameiros, Rhodes, British Museum A 748 (late seventh century BC)[69] Fig. 3. Winged Gorgon with volute nose, wide mouth, tusks/fangs, tongue, and beard, as Mistress of Animals flanked by geese; plate from Kameiros, Rhodes, British Museum A 748 (late seventh century BC)[69]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8sxe!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5cf173d8-6257-4706-b783-1d97a55fd041_1920x1920.jpeg)

my name means honeybee in greek, so i am particularly fond of this article.ty